React Native Performance Cookbook

React Native Performance Cookbook¶

Overview¶

The purpose of this document is to describe common performance issues encountered while developing React Native apps, and ways in which they can be mitigated.

Unnecessary or excessive re-renders¶

In my experience the most frequent cause of poor performance in a React Native app is excessive re-renders. While not always the root cause, I generally start here when diagnosing sluggish behavior.

One important nuance to keep in mind is that even though the user is able to scroll around in a React Native app, the actual JS runtime may be “frozen,” doing computationally expensive work on the main thread, blocking the message queue and not processing input events. This is because the actual view is rendered by the native runtime, in a different thread, so the app doesn’t appear completely frozen to the end user.

Here’s a short video to demonstrate the issue — notice that when the JS FPS graph flat-lines the view can still be scrolled around because this gesture is handled by the pure native layer. Item-level touch events, however, don’t work until the JS FPS recovers and can start handling input again:

Visualizing re-renders¶

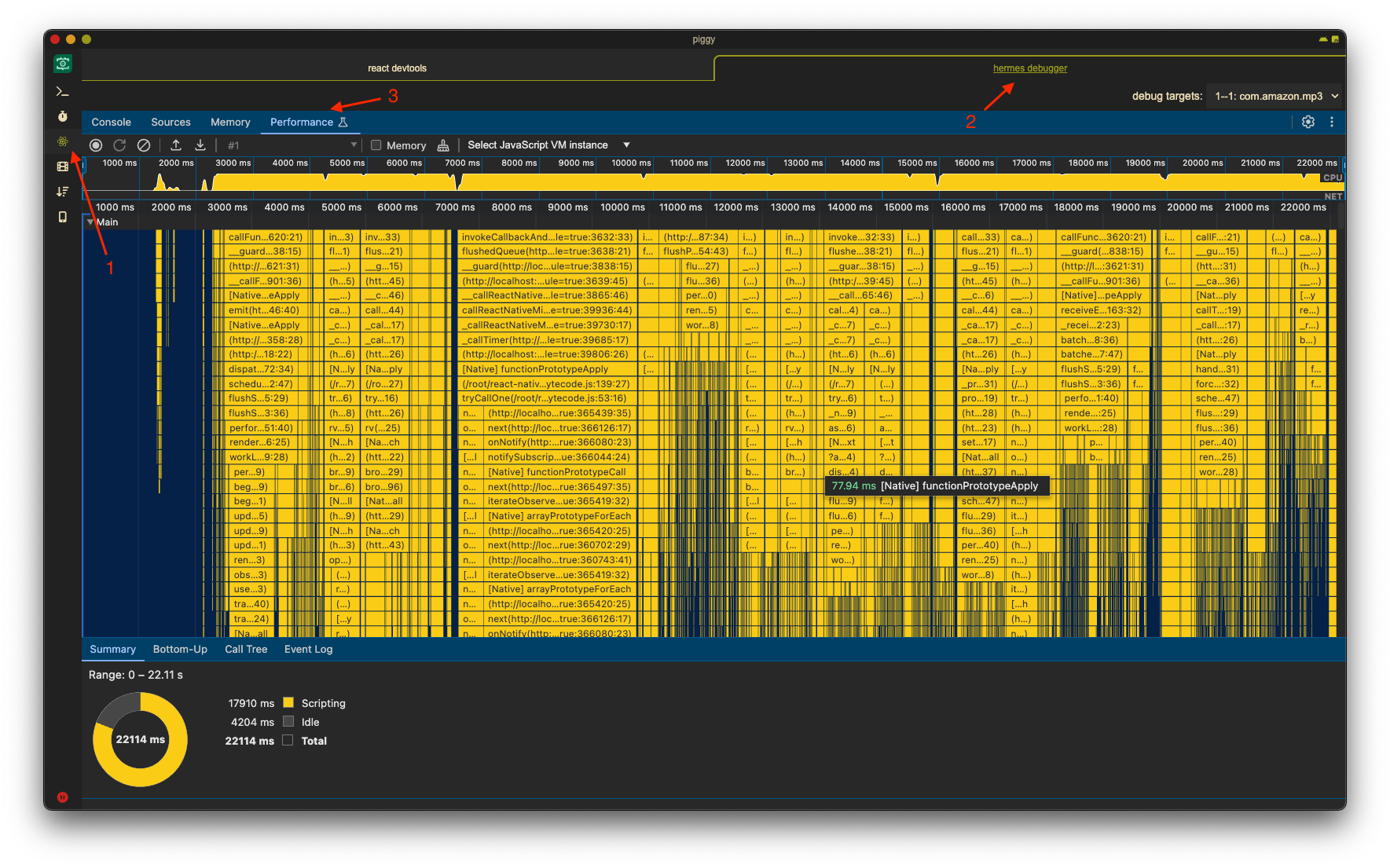

We can use react-devtools to figure out how many times components were re-rendered, and in some cases, why. Here’s an example using the same screen as above. We can see 232 renders occurred while the screen was loading:

react-devtools is available in all versions of piggy, but can also be installed as a standalone app.

If you’re interested in an in-depth example that demonstrates how to use these tools to debug performance issues you can refer to the following article: Window Size: Performance Investigation V2.

Programmatically profiling re-renders¶

React provides a special <Profiler> component that can be used to measure rendering performance programmatically. It allows developers to obtain much of the same information in the aforementioned section about react-devtools.

Documentation can be found here: https://react.dev/reference/react/Profiler

Data dependencies and referential equality¶

Before diving into ways to mitigate re-renders it’s important to understand that React uses referential equality when detecting state changes to determine if something should be rendered. In general, React will re-render a component when any of the data it depends on changes. Data dependencies are usually, but not strictly, a combination of “props” (data provided by a parent component) and “state” (data encapsulated within the component itself).

React effectively remembers all of the values of the state used in the previous render, and then compares it to current state. If anything has changed, the component is re-rendered. When comparing previous state to current state React will use referential equality for complex data types like arrays, objects and functions. Said another way, it uses the === operator. That means that two arrays arrays with the same values are not necessarily equal. For example:

const a = 1

const b = 1

a === b /* true! */

const c = "this is a string"

const d = "this is a string"

c === d /* true */

const e = [1, 2, 3]

const f = [1, 2, 3]

e === f /* false! same data, different instances. */

const g = { foo: 'bar' }

const h = { foo: 'bar' }

g === h /* false! same data, different instances. */

const i = () => { console.log("foo") }

const j = () => { console.log("foo") }

i === j /* false! same functionality, different instances. */

This is a common, and sometimes unexpected cause of re-renders. Here’s a concrete example:

const ParentComponent = () => {

const ids = [1, 2, 3];

/* ChildComponent will be re-rendered every time we render, because

a new instance of the 'ids' array is created every time this function

is evaluated */

return <ChildComponent ids={ids} />

}

Every time the ParentComponent renders it instantiates a new ids array with the same values. Even though they contain the same contents, they are different when compared using the equality operator.

The following sections on memoization will explore this problem in more detail and discuss common solutions.

React.memo¶

Remember a couple paragraphs ago when I said child components will not be re-rendered if their data dependencies don’t change? Well… that’s not quite true, at least not out of the box.

By default a child component will re-render any time its parent is re-rendered. In other words, if a component renders, so do all of its children, potentially recursively.

Additionally, when a parent renders a child it will provide the most up to date props to the render function. Even if the child doesn’t actually render new data, the render function is still evaluated. That means logic will still execute — hooks will still evaluate, computations will still occur, etc.

To avoid event evaluating child component render functions we can use the React.memo higher-order-component. Internally, it will track props provided by the parent and not call the actual implementation if data supplied by the parent hasn’t actually changed.

Usage is simple — we just wrap our functional component with React.memo()

const _ChildComponent = () => {

/* .... */

return (<div>...</div>)

}

export const ChildComponent = React.memo(_ChildComponent)

Or, more compactly:

export const ChildComponent = React.memo(() => {

/* .... */

return (<div>...</div>)

})

General guidance:

It’s a good idea to wrap “non-trivial” components with React.memo. The definition of “non-trivial” is a bit nebulous, but in general, consider using React.memo if the component:

Contains more than a few sub-components, transitively.

Does anything computationally expensive (e.g. searching, sorting, evaluating a bunch of hooks, etc)

May be part of a view hierarchy where the parent renders frequently, but the data provided to the child doesn’t change often.

For advanced use cases you can provide React.memo() a custom comparison function as a second argument, which will be used instead of the default referential equality check. It will be provided prevProps and nextProps values that you can use to determine if the component should be re-rendered.

useMemo, useCallback¶

Unfortunately React.memo is not a silver bullet, as it depends on parent components playing nice and not passing props to children that are logically, but not referentially equal.

Playing nice as a parent component generally requires thoughtful usage of the useMemo and useCallback hooks. Both of these are used to return “memoized” (i.e. “cached”) values for non-simple data types.

Let’s take a look at an example that does not take advantage of either of these, discuss the problems, then see how we can fix the issues.

const ParentComponent = () => {

const names = ['Homer', 'Marge', 'Bart', 'Maggie', 'Lisa']

const handleClick = (name: string) => {

alert(`${name} is at index ${names.indexOf(name)}`)

}

return <List items={names} onItemClick={handleClick} />

}

In this case both names and handleClick are re-created every time this component is rendered, and the new instances are passed to the <List> component. That means even if the <List> is wrapped with React.memo(), and even though the state is logically the same as the the previous render, referential equality is broken and the <List> will re-render.

Let’s see how we can apply useMemo and useCallback to avoid this issue:

const ParentComponent = () => {

/* the function passed to 'useMemo' will only evaluate when any of

the values passed in the array in the second argument change. Because

no dependencies are passed, it will only ever run once */

const names = useMemo(() => {

return ['Homer', 'Marge', 'Bart', 'Maggie', 'Lisa']

}, [])

/* similarly, the value returned by 'useCallback' will only change when

one or more of the values in the dependency array change. In this case

the only dependency is 'names', and 'names' never changes, so the

same callback instance will always be used */

const handleClick = useCallback((name: string) => {

alert(`${name} is at index ${names.indexOf(name)}`)

}, [names])

/* now that 'items' and 'handleClick' are correctly memoized, the List

component should not re-render (assuming it has been wrapped with

'React.useMemo') */

return <List items={items} onItemClick={handleClick} />

}

This is a relatively simple example, but there are some more nuanced situations where it’s not as immediately obvious that referential equality is being broken between renders. Consider this example:

const ParentComponent = () => {

...

/* useQuery() may take a while to complete... */

const { data } = useQuery(...)

const items = data?.names ?? []

...

return <List items={items} />

}

Can you spot the bug? It’s the empty array. ParentComponent will re-render automatically whenever useQuery completes so we can extract the data and pass it to the underlying <List>. But what if ParentComponent re-renders for any other reason while useQuery is in flight? That’s right, a new empty array will be created and passed to <List> via props, which will cause a render.

Here are a couple different ways to work around this particular issue:

/* with a static empty array */

const EMPTY_ARRAY = [] /* only created once */

const ParentComponentStaticArray = () => {

const { data } = useQuery(...)

const items = data?.names ?? EMPTY_ARRAY

return <List items={items} />

}

/* with useMemo */

const ParentComponentUseMemo = () => {

const { data } = useQuery(...)

const items = useMemo(() => {

return data.names ? data.names : []

}, [data.names])

return <List items={resolvedItems} />

}

/* with useState and useEffect */

const ParentComponentUseState = () => {

const [resolvedItems, setResolvedItems] = useState([])

const { data } = useQuery(...)

const items = data?.names

useEffect(() => {

if (data.names) {

setResolvedItems(data?.names)

}

}, [data?.names]

return <List items={resolvedItems} />

}

All of these are valid ways to fix the issue, so choose the most reasonable one for your task at hand.

General guidance:

Use useMemo and useCallback liberally, especially in heavy weight parent components that pass props to children. Doing so will help avoid unnecessary re-renders for components that are wrapped in React.memo().

rules-of-hooks lint rule¶

In order for memoization to work properly it’s incredibly important to make sure you are passing the full set of dependencies to your useMemo / useCallback / useEffect hook calls.

The Dragonfly app enforces the react-hooks/rules-of-hooks lint rule, which will analyze hook dependencies and raise an error if anything is missing or extraneous. There are rare cases where you may need to violate this rule, but generally only if you know what you’re doing, and have a very good reason (i.e. be ready to thoroughly defend your decision during code review).

General guidance:

If you find yourself trying to ignore this lint rule, just remember that you’re almost certainly doing something wrong.

Be careful with useState¶

The useState hook is a powerful tool for retaining state across component re-renders, but it needs to be used with care. As a reminder, the useState() hook returns an array of two values — the first is the tracked state itself, the second is a function to update the state.

When the set function is called, the tracked state is updated, then the component is re-rendered so the updated value can be applied to the component hierarchy. Let’s look at an innocuous example:

const ParentComponent = () => {

const [enabled, setEnabled] = useState(false)

const handleClick = useCallback(() => {

/* the work to track the updated enabled state is actually batched

and performed asynchronously. When it completes, this component

instance will be re-rendered with the updated value */

setEnabled(!enabled)

}, [enabled, setEnabled])

return (

<View>

<Button onClick={handleClick} />

<MyWidget enabled={enabled} />

<View>

)

}

This example is fine. It uses a piece of tracked state to indicate whether a component should be enabled or disabled. It uses setState``() so it can remember this value across renders. No concerns here.

However, let’s consider a more complex example where a parent component is listening to scroll events, then updating a child component based on the scroll position:

const ParentComponent = () => {

const [scrollPosition, setScrollPosition] = useState(0)

/* when the user scrolls this callback will be called multiple

times per second */

const handleScroll = useCallback((x, y) => {

/* we call setScrollPosition() so <TopBar> will be re-rendered

with the updated value. While this works, it is very heavy

handed because it causes ParentComponent to re-render entirely,

including all *other* child components: Shoveler, Description,

and List */

setScrollPosition(y)

}, [setScrollPosition])

return (

<ScrollView onScroll={handleScroll}>

<TopBar scrollPosition={scrollPosition} />

<Shoveler />

<Description />

...

<List />

</ScrollView>

)

}

Note that although the example above is pseudocode, it’s modeled after a real-world example that can be found here: https://gitlab.aws.dev/amazonmusic/musicdragonfly/dragonfly/-/merge_requests/4641

There are different ways to address this particular issue, but the following shows how it was actually implemented, at a high level:

const TopBar = React.forwardRef<>(({ props }, ref) => {

const [scrollPosition, setScrollPosition] = useState(0)

/* useImperativeHandle allows us to define an imperative API to be attached

to the ref value that's returned. In this case our API is a single method

called `setScrollPosition` that delegates to the state setter above. Doing

this allows a parent component to update our state directly without prop

drilling or full-tree re-renders. */

useImperativeHandle(ref, () => ({ setScrollPosition }, [setScrollPosition])

}

const ParentComponent = () => {

const topBarRef = useRef()

const handleScroll = useCallback((x, y) => {

/* update the position state directly in the TopBar instance,

which avoids re-rendering this component. The setPosition method is

added to the ref via 'useImperativeHandle' above. */

topBarRef.current?.setPosition(y)

}, [topBarRef])

return (

<ScrollView onScroll={handleScroll}>

<TopBar ref={toolbarRef} />

<Shoveler />

<Description />

...

<List />

</ScrollView>

)

}

General guidance:

If a component needs local state to operate:

It should prefer to obtain and encapsulate that state itself, instead of having it supplied by an ancestor (aka “prop drilling”).

If the state must be supplied via ancestor, consider the mechanism by which the state data is stored and propagated.

If state is updating frequently, consider not using

setState()in the parent component.If possible, avoid prop drilling to avoid unnecessary re-renders all the way down the view hierarchy.

Resource contention¶

Sluggish app performance is often related to some sort of resource contention, e.g. the CPU thread is blocked, the garbage collector is constantly running, the disk is thrashing, etc.

You can use standard tools to perform CPU profiling and capture JS heap dumps. For web builds you can use the version of the developer tools already integrated into your browser, and for mobile builds you can use the Hermes debugger integrated into piggy.

Native Module (bridge) traffic¶

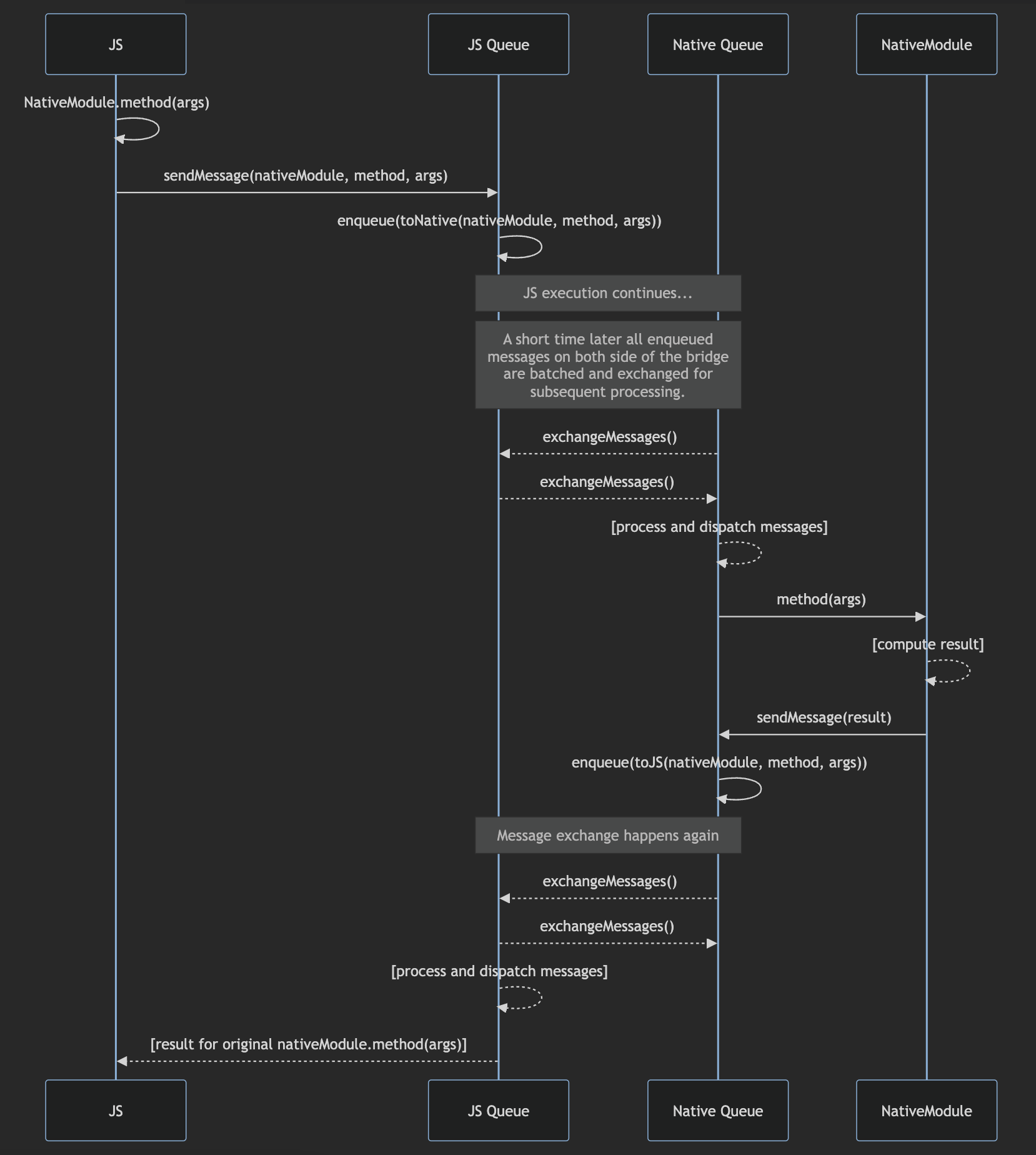

When Javascript needs to communicate with the native layer, or vice versa, messages are exchanged through a communication channel called the “bridge.”

Messages are simple JSON objects.

Here’s a sequence diagram that illustrates message passing and data flow between runtimes:

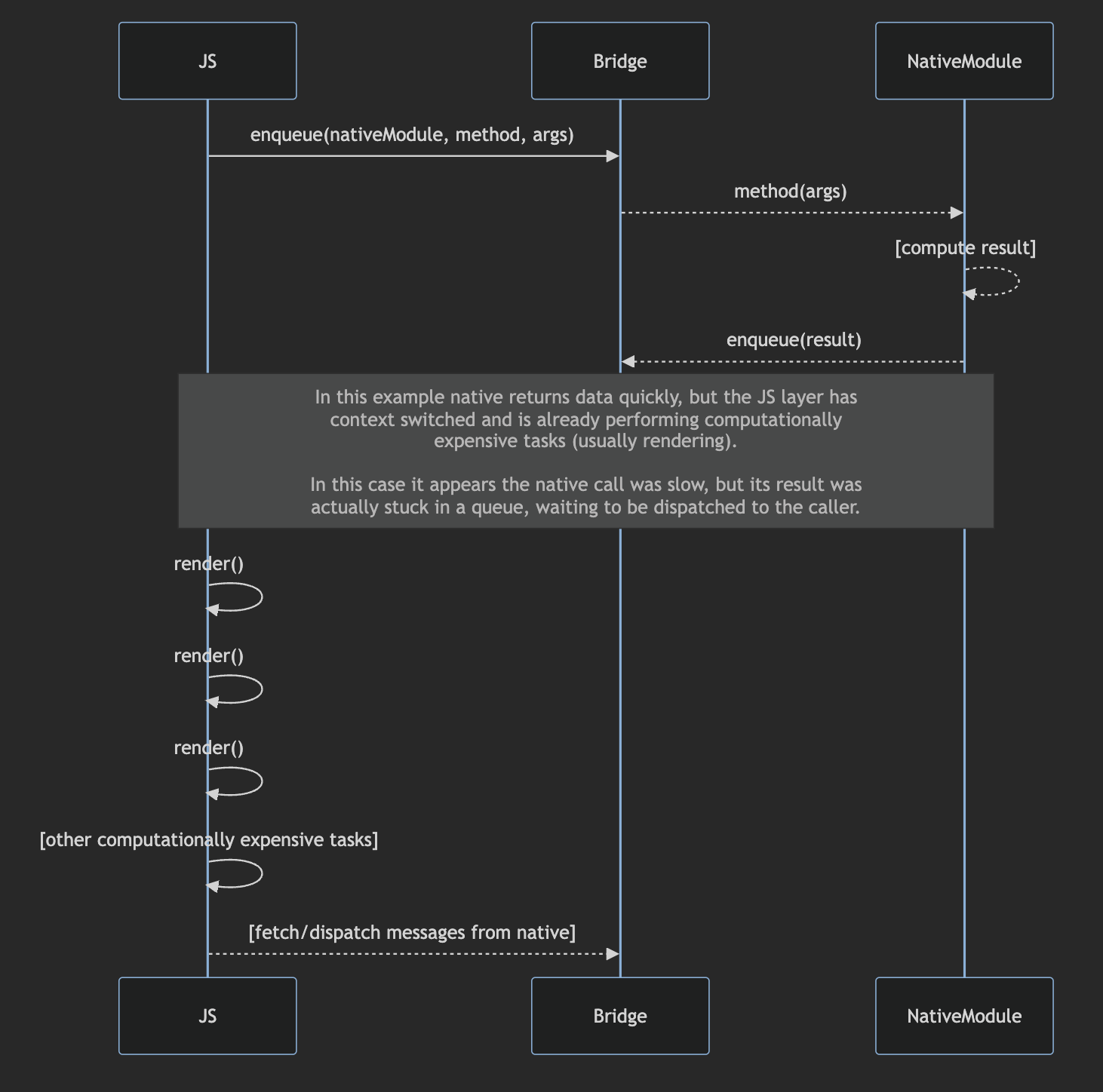

Because the JS runtime is single threaded, all messages to and from the native layer are dispatched and routed on the same thread that is responsible for rendering components, evaluating hooks, performing view reconciliation (and all other logic written by experience teams). A consequence of this design is that it’s very easy for JS code to introduce significant latency for native module call round trips, as illustrated by the following diagram:

It’s also possible, but less likely, for the native layer to cause delays in rendering by flooding the bridge with messages to Javascript, causing the dispatch/processing phase of message handling to hold the CPU for long periods of time. However, there are certainly opportunities to introduce these sorts of inefficiencies — one example is publishing playback position events multiple times a second.

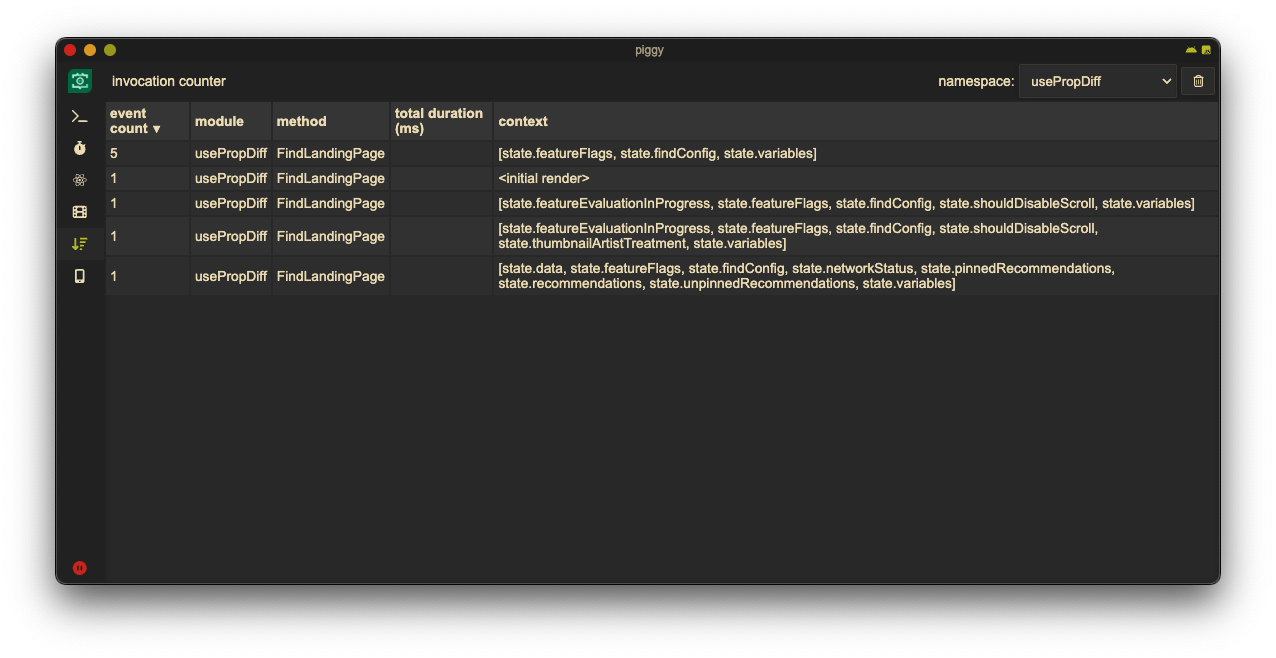

If you use piggy you can use the “Invocation Counter” tool to spy on the bridge to see how many native module calls are being made, in real time, as the app runs:

General guidance:

Avoid using native modules and the message bridge if you can. Even fast calls can be slow (in wall-clock time) if the request or response gets stuck behind other slow tasks in the message queue.

If you do need to interoperate with the native layer over the bridge, you should consider the bridge to be a high-latency, high-bandwidth communication channel. In other words, you should generally prefer fewer messages with larger data payloads to many small messages.

Additionally, you should always benchmark your native module calls to understand how many times they are invoked, and how long they generally take to return.

Apollo cache and fetch policies¶

Data retrieved via remote service calls (e.g. Firefly) should be aggressively cached and refreshed asynchronously, on-demand; doing so helps ensure initial page renders occur as quickly as possible, while ensuring data is relatively up to date. In general, experience code should rely on the the built-in caching mechanisms provided by the Apollo Client.

When executing a query, the caller can specify something called a “fetch policy,” which may be one of the following, pulled directly from the Apollo docs:

cache-first: return result from cache. Only fetch from network if cached result is not available.cache-and-network: return result from cache first (if it exists), then return network result once it’s available.cache-only: return result from cache if available, fail otherwise.no-cache: return result from network, fail if network call doesn’t succeed, don’t save to cachenetwork-only: return result from network, fail if network call doesn’t succeed, save to cachestandby: only for queries that aren’t actively watched, but should be available forrefetchandupdateQueries.

Queries, by default, use cache-first which is non-ideal for most use cases, as data displayed within our app often has state or metadata that may change frequently — “in library” and “like” status for example.

We generally recommend using cache-and-network to ensure a page can render immediately if there is any version of the required data cached, then update it over the network asynchronously.

Often when we try to render a page only some of the required data is cached, but not everything. In these cases a caller may specify returnPartialData: true in the query and it will immediately return the fields that are available in cache, then make a network request to resolve the rest. While this does potentially increase code complexity (because components can not assume the data they need is available), it can be a very useful performance optimization in some cases, depending on product requirements.

Use appropriately sized images¶

Images are another frequent cause of performance issues in mobile apps. Using images that are larger than their display size uses extraneous network bandwidth, more memory, and increases CPU load. Using images that are too small result in a lower-fidelity customer experience.

General guidance:

If your experience is displaying images, ensure that:

The images you are displaying are being served via media central.

You are displaying it using an image component provided by the Bauhaus library.

As long as the aforementioned criteria are met, Dragonfly will automatically request exact-sized (or very-closely-sized) images from the CDN, which will be resized and cached on the backend to avoid extraneous resource usage on the client. If you’re interested in how this is implemented you can see this doc: Dragonfly Image Size Optimization.

If, for some reason, you cannot use Bauhaus, you should still try to serve your images from media central, then leverage its transformation API to download right-sized images: https://w.amazon.com/index.php/MSA/HowTo/ImageStyleCodes.

Think about your layouts¶

Try to avoid deep, complex view hierarchies¶

React, like many other declarative UI frameworks, encourages deeply nested, well-encapsulated component hierarchies. Broadly (and subjectively) speaking, this approach to writing front-end applications results in code that is more modular and easier to reason about when compared to their imperative counterparts.

As with anything, this style of application architecture comes with tradeoffs. Complex, deeply nested view hierarchies, especially those that use dynamic layout algorithms (e.g. flexbox) are usually much more computationally expensive to calculate than simple, flat layouts using basic constraints. That’s because:

In order for a parent view to layout its children properly, all of the children of the children must first be laid out properly, recursively.

Dynamic layout algorithms like flexbox are multi-pass in many situations, meaning it often requires iterating over all children multiple times to derive correct positioning information.

General guidance

If you are having performance issues due to complex layouts:

Experiment with restructuring your layout to be less nested. Be aware, this can come at the cost of code complexity, so it can be tricky to find a healthy balance while keeping your code idiomatic.

Look for opportunities to use Fragments to avoid unnecessary wrapper views.

Use virtualization, if possible (see below).

Take advantage of “virtualization”¶

Virtualization refers to the concept of only computing and rendering views that are visible to the user. If we have a list widget that has hundreds of thousands of rows, we don’t want to render all of them — that would waste a ton of memory and CPU cycles.

React Native provides a virtualized list component called FlatList, and Shopify has their own implementation called FlashList. Bauhaus provides wrappers for both of these: BauhausFlatList, BauhausFlashList.

General guidance

If you’re displaying either (a) a large list of data, and/or (2) a moderately-sized list of data with complex row views, you should almost always use virtualization to reduce memory consumption and CPU usage, and usually increase scrolling frame rate. In most cases, either a FlatList or FlashList will suffice, but you should familiarize yourself with both and choose the best one for the task at hand.

Avoid React.Context¶

React.Context is a powerful and convenient tool that allows parent components to provide child components state without requiring explicit prop drilling. It does, however, have an unfortunate side effect for performance: any time a Context value updates, every child component is re-rendered unconditionally.

Consider the following example that uses a Context to supply a value containing a count property to all child components:

const ValueContext = React.createContext({ count: 0 });

const C1 = () => {

const { count } = useContext(ValueContext)

return <div>{`C1 ${count}`}</div>

}

const C2 = () => {

return <div>{'C2'}</div>

}

const C3 = () => {

return <div><C2 /><div>{`C3`}</div></div>

}

export default function App() {

const [value, setValue] = useState({ count: 0 });

const handleClick = useCallback(() => {

setValue({ count: value.count + 1 })

}, [value, setValue])

return (

<div>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Increment Count</button>

<ValueContext.Provider value={value}>

<C1 />

<C3 />

</ValueContext.Provider>

</div>

);

}

Intuitively you may only expect the <C1> component to re-render when the user presses the “Increment Count” button because it’s the only one consuming the value from the context. However, both <C2> and <C3> components will render as well.

Appendix 1: installing piggy¶

Many sections of this document reference a tool called piggy that can be used to perform various types of performance troubleshooting. You can install and launch it as follows:

cd /path/to/dragonfly-src

yarn signin

npx dragonfly piggy install

npx dragonfly piggy start

Appendix 2: debugging re-renders with usePropDiff¶

Sometimes it can be tricky to figure out why something is re-rendering, even when we understand all of the common causes. Components can be complex, or live in complex hierarchies, and it’s not always straight forward figuring out what properties or state are actually changing.

Dragonfly includes a hook called usePropDiff that can help you figure out what is causing your component to re-render by comparing state between re-renders, emulating React’s shallow / referential equality checks.

const DemoComponent = (props) => {

const { prop1, prop2 } = props

const [state1, setState1] = useState('foo')

const [state2, setState2] = useState('bar')

const visibilityContext = useContext(VisibilityContext)

const memoizedValue = useMemo(() => {

return `${state1} ${state2}`

}, [state1, state2])

const handleClick = useCallback((event) => {

setState1(event.value)

}, [setState1])

/* ... */

/* pass all data dependencies that could change and

cause a re-render to the hook. generally this includes

props provided by an ancestor, context values consumed,

and any locally tracked state that persists across

render invocations. */

usePropDiff({

componentName: 'DemoComponent',

compare: {

props,

state: {

state1,

state2,

memoizedValue,

handleClick,

},

context: {

visibilityContext,

}

},

})

return (<View> /* ... */ </View>)

}

During a render pass, if one of the specified properties has changed, usePropDiff will log information to the console that contains the name of the changed property and the previous and next values.

[usePropDiff] DemoComponents dependencies changed (callCount=9) [

{

name: 'props.foo',

currValue: { /* value during this render */ },

lastValue: { /* value from previous render */ }

},

{

name: 'state.state1',

currValue: { /* value during this render */ },

lastValue: { /* value from previous render */ }

}

...

]

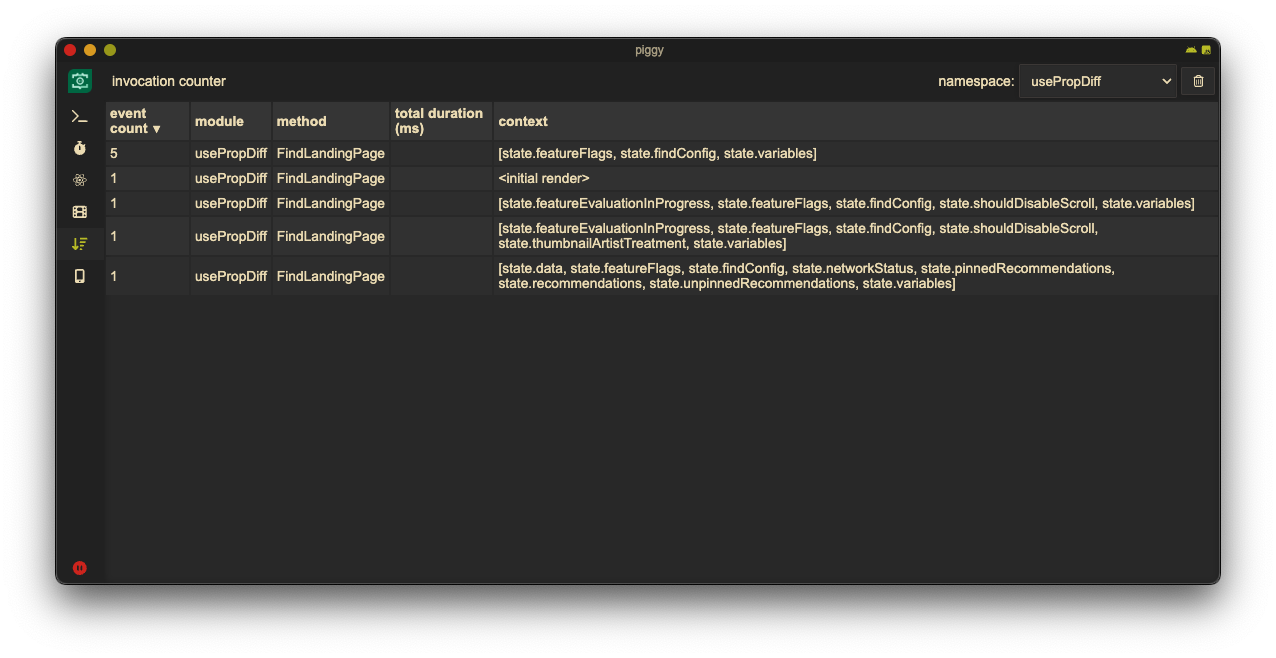

If you’re using piggy you can get a quick overview of changes detected by usePropDiff in the “invocation counter” tool — just select the usePropDiff namespace; the context column will list the names of all properties that have changed between renders.

Unfortunately this is not a silver bullet, as hooks used by the component may run side effects that cause the component to re-render, for example by internally calling setState after some asynchronous action completes. It is, however, a useful tool to have at your disposal.